Go Seigen vs. Fujisawa Kuranosuke - Breakdown

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f4_M4KJvN-U]

Nonsemble performing part Ic

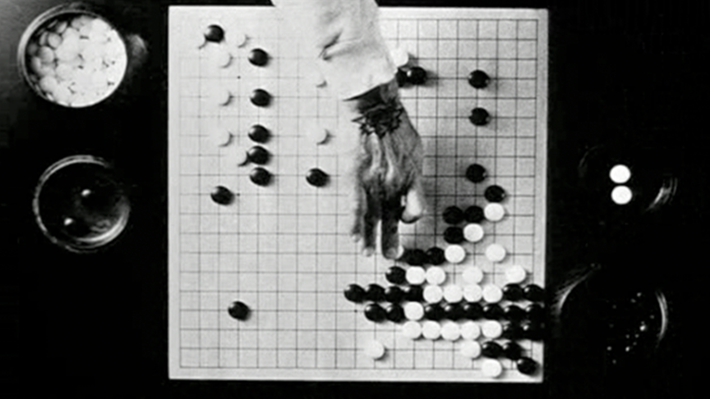

Go Seigen vs. Fujisawa Kuranosuke is a 30 minute work for chamber septet, using the moves of 1953 championship game of Go as stimulus for harmonic, rhythmic and melodic material. It's an experiment in extracting musical ideas from abstract patterns and sequences, and allowing these ideas to develop intuitively into a large-scale work. Of the larger works I've composed, Go is the most detailed and the most unified. While previously I've written complementary pieces and stitched them together to become movements of a larger work, this time everything in the work is grown from the same materials, and everything in it is connected to everything else. Go is a fascinating game. You might have seen it played in the Darren Aronofsky film Pi. It was invented by the Chinese thousands of years ago, and spread to Japan where it has been elevated to a fine art, and maybe even a kind of science. The game is played on a gridded board with small black and white pieces, so in that sense it is similar to chess. However the sheer infinity of combinations allowed by its relatively simple rules make it many times more complex.

Go in the film Pi

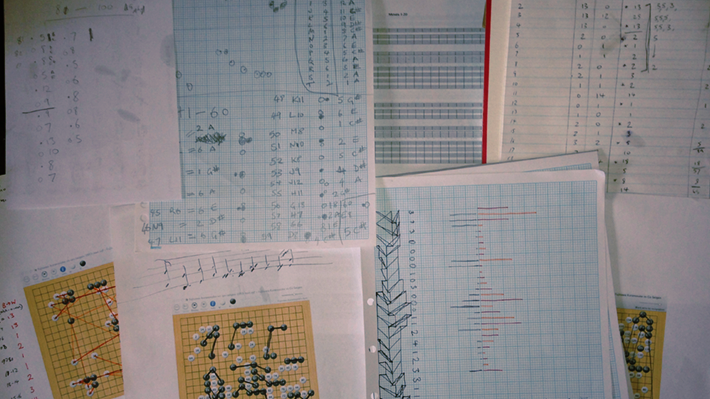

Go Seigen is considered to be the greatest Go player of the 20th century. He was born in China, and migrated to Japan where he received the Japanese name by which we know him. Because Go is a game of skill with zero element of chance, players' skill levels are rigorously ranked using the tiered "dan" system. By 1953, Go Seigen and Fujisawa Kuranosuke (later to be known as Fujisawa Hosai) were the first and only two players to have reached the level of 9-dan, so this match was really the best of the best. Though Fujisawa played a strong game, Go Seigen won, solidifying his place as the greatest living Go player. Here's a play by play analysis of the actual game, for the real sports fans out there. [vimeo 61602189 w=560 h=420] The Greatest Games Ever Played 01 from countsheep on Vimeo.I'm drawn to the game of Go because it combines two of my major interests: Japanese culture, and complexity or chaos that emerges from simple processes. Go operates on simple rules - if your stones are surrounded by the enemy, they die. It's a little more complicated than that obviously, but the rest of the rule book and the mountains of literature which accompany it basically emerge from this one principle. Similarly, any single match generates reams of new information, all based on this simple rule.This abundance of data is actually what ended up being the biggest challenge in creating this work. The compositional challenge I'd set myself was to use patterns from the game to generate material - melodies, harmonies, rhythms, anything. But the list of 168 documented moves in the game could be looked at in so many different ways to produce so much detail, the piece ran the risk of being a meandering hour-long string of unintelligible, non-repeating patterns. The moves could be looked at in sequence, in their positions on the board, their distance from each other, their relative danger or safety, and any number of more abstract ways. The first phase of composition became about freely playing with the patterns to see what would emerge. I started making diagrams and number lists to try and convert the patterns into music. The approaches I tried tended to mostly end up sounding very jarring and unnatural, which was not the aesthetic I was after. This piece isn't about revealing the hidden beauty of the numbers, but more of an experiment into stimulating musical creativity with complex patterns. Occasionally I would cook up a system for interpreting the moves which resulted in aesthetically pleasing patterns, which translated readily into a rhythm or a melody. These happy accidents quite often wound up as the recurring motifs you hear in the piece.  At a certain point it became necessary to step away from the Go board, and to continue developing the materials I had in a more intuitive way. This involved envisioning the kind of journey I wanted the piece to go on, and trying to see the potential in the various chunks of rhythms, melodies and harmonies that I'd extracted from the Go board. There was a point about halfway through the process when listening to a Godspeed You! Black Emperor record prompted me to trash most of what I had, and question whether I really knew anything about long-form composition at all. In fact, short digression: there's been many times during this process where I've felt like I really hit the edge of my abilities. It's great when something drives you to throw up your hands and say "I actually know nothing." Because it becomes necessary to learn, expand, and grow in order to move forward. Music is just music of course, and I hate talking about composing as if it's anything like going to war or nursing an ill relative or raising a child… But I think this composition has challenged me more than any before it.Anyway, Godspeed's Allelujah! Don't Bend! Ascend! album was the catalyst which pushed me in the final direction, not because I wanted my work to sound like Godspeed, but because it made me realise something about sustaining interest for long periods of time. Developing a small amount of material very patiently and resolutely can be so much more effective than flittering between many contrasting ideas. The process then became about repetitively cutting material which was least interesting, and developing the remaining material in its place, sometimes in unexpected and exciting directions. It was more of a process of evolution than creation, as certain species of ideas died off and the stronger ones grew to take their place. A number of other things I was listening to also really influenced the sound; Talk Talk, John Adams, Mouse on the Keys, William Britelle, Flying Lotus, Sufjan's Age of Adz and a load of other stuff was buzzing around me at the time of writing. For the last few years I have been studying a PhD under the supervision of the exceptional Brisbane composer Robert Davidson, so his influence has infiltrated strongly, as well as the work of my peers in the PhD program, especially Leah Kardos and Thomas Green.The work eventually took shape as three main movements, each in a kind of ternary form, surrounded by a prelude and postlude. The first and last sections of each main movement are similar - sort of like variations of each other. These are always separated by a contrasting middle section which in most cases takes up somewhere a little more murky and uncertain, before returning to a new variation on the ideas of the first section. | Prelude (90bpm) | | Ia (144bpm) | Ib (96bpm) | Ic (144bpm) | | IIa (105bpm) | IIb (75bpm) | IIc (105bpm) | | IIIa (80bpm) | IIIb (100bpm) | IIIc (90bpm) | | Postlude (60bpm) |There are a few recurring motifs in the work. The long rhythmic motif based on variations and extensions of a basic 5/4 rhythm was pulled numerically from the go moves, and underpins a great deal of the rhythmic and melodic material in the piece. The most noticeable perhaps is the fast-moving theme in Ia and the patterns at the beginning of IIIa. There is also the lyrical melodic theme, which appears in its in original incarnation at the very end of the piece, in IIIc, but pops up in various disguises throughout. This theme was constructed using the positions of stones on the board at a particular point in the game to define the shape and harmonisation of the melody. The harmonic structure is fairly freeform - I've focused more on making the harmony work well locally, and pretty much ignored the idea of large-scale harmonic structure, ending movements in the same key as they started etc (I adopted this approach after reading research which showed that tonic resolution just isn't cognitively perceptible on such a long-term scale). However in place of that, I've approached tempos with a kind of classical attitude, in the sense that tempos tend to be related in whole-number ratios. For example, Movement 1 starts at 144bpm, changes to 96bpm (a metric modulation where the previous quaver becomes the new quaver triplet), and returns to 144. Relate this to pitch frequency ratios, and it is the rhythmic equivalent of modulating to the 5th, and back again, in classic sonata style.

At a certain point it became necessary to step away from the Go board, and to continue developing the materials I had in a more intuitive way. This involved envisioning the kind of journey I wanted the piece to go on, and trying to see the potential in the various chunks of rhythms, melodies and harmonies that I'd extracted from the Go board. There was a point about halfway through the process when listening to a Godspeed You! Black Emperor record prompted me to trash most of what I had, and question whether I really knew anything about long-form composition at all. In fact, short digression: there's been many times during this process where I've felt like I really hit the edge of my abilities. It's great when something drives you to throw up your hands and say "I actually know nothing." Because it becomes necessary to learn, expand, and grow in order to move forward. Music is just music of course, and I hate talking about composing as if it's anything like going to war or nursing an ill relative or raising a child… But I think this composition has challenged me more than any before it.Anyway, Godspeed's Allelujah! Don't Bend! Ascend! album was the catalyst which pushed me in the final direction, not because I wanted my work to sound like Godspeed, but because it made me realise something about sustaining interest for long periods of time. Developing a small amount of material very patiently and resolutely can be so much more effective than flittering between many contrasting ideas. The process then became about repetitively cutting material which was least interesting, and developing the remaining material in its place, sometimes in unexpected and exciting directions. It was more of a process of evolution than creation, as certain species of ideas died off and the stronger ones grew to take their place. A number of other things I was listening to also really influenced the sound; Talk Talk, John Adams, Mouse on the Keys, William Britelle, Flying Lotus, Sufjan's Age of Adz and a load of other stuff was buzzing around me at the time of writing. For the last few years I have been studying a PhD under the supervision of the exceptional Brisbane composer Robert Davidson, so his influence has infiltrated strongly, as well as the work of my peers in the PhD program, especially Leah Kardos and Thomas Green.The work eventually took shape as three main movements, each in a kind of ternary form, surrounded by a prelude and postlude. The first and last sections of each main movement are similar - sort of like variations of each other. These are always separated by a contrasting middle section which in most cases takes up somewhere a little more murky and uncertain, before returning to a new variation on the ideas of the first section. | Prelude (90bpm) | | Ia (144bpm) | Ib (96bpm) | Ic (144bpm) | | IIa (105bpm) | IIb (75bpm) | IIc (105bpm) | | IIIa (80bpm) | IIIb (100bpm) | IIIc (90bpm) | | Postlude (60bpm) |There are a few recurring motifs in the work. The long rhythmic motif based on variations and extensions of a basic 5/4 rhythm was pulled numerically from the go moves, and underpins a great deal of the rhythmic and melodic material in the piece. The most noticeable perhaps is the fast-moving theme in Ia and the patterns at the beginning of IIIa. There is also the lyrical melodic theme, which appears in its in original incarnation at the very end of the piece, in IIIc, but pops up in various disguises throughout. This theme was constructed using the positions of stones on the board at a particular point in the game to define the shape and harmonisation of the melody. The harmonic structure is fairly freeform - I've focused more on making the harmony work well locally, and pretty much ignored the idea of large-scale harmonic structure, ending movements in the same key as they started etc (I adopted this approach after reading research which showed that tonic resolution just isn't cognitively perceptible on such a long-term scale). However in place of that, I've approached tempos with a kind of classical attitude, in the sense that tempos tend to be related in whole-number ratios. For example, Movement 1 starts at 144bpm, changes to 96bpm (a metric modulation where the previous quaver becomes the new quaver triplet), and returns to 144. Relate this to pitch frequency ratios, and it is the rhythmic equivalent of modulating to the 5th, and back again, in classic sonata style.  At the time of writing, Go is in rehearsals toward its premiere performance at Dots+Loops on March 22. It's been a massive project, and it is incredibly satisfying to see it being assembled by real musicians. The players in Nonsemble have been incredibly important in giving me advice, feedback, and support, as well as being committed to making the piece work despite its cumbersome length and (at times) difficulty. It's an honour to have such a talented bunch taking my music seriously enough to dedicate such time to it. I feel like Go is a turning point in my compositional practice toward new levels of detail, unity, and awareness of the capabilities of the instruments; I'm definitely just a little bit proud of it. Usually when I finish a work, I feel like moving on immediately, but I feel like I can sit with this one for a bit - surely that's a good sign.Go Seigen vs. Fujisawa Kuranosuke is now available to download in full at http://bit.ly/1HlWfLb.[bandcamp width=100% height=120 album=1108520643 size=large bgcol=ffffff linkcol=333333 tracklist=false artwork=small]

At the time of writing, Go is in rehearsals toward its premiere performance at Dots+Loops on March 22. It's been a massive project, and it is incredibly satisfying to see it being assembled by real musicians. The players in Nonsemble have been incredibly important in giving me advice, feedback, and support, as well as being committed to making the piece work despite its cumbersome length and (at times) difficulty. It's an honour to have such a talented bunch taking my music seriously enough to dedicate such time to it. I feel like Go is a turning point in my compositional practice toward new levels of detail, unity, and awareness of the capabilities of the instruments; I'm definitely just a little bit proud of it. Usually when I finish a work, I feel like moving on immediately, but I feel like I can sit with this one for a bit - surely that's a good sign.Go Seigen vs. Fujisawa Kuranosuke is now available to download in full at http://bit.ly/1HlWfLb.[bandcamp width=100% height=120 album=1108520643 size=large bgcol=ffffff linkcol=333333 tracklist=false artwork=small]